Introduction

As a result of its popularity and rapid spread, English has become a global language of education (Crystal, 2003) and science (Mukminatien, 2012) which is considered crucial for the future of young people (Spolsky, 2004). This phenomenon has had a great impact on academic institutions in non-English speaking countries especially in East Asia where an educational policy using English Medium Instruction (EMI) has been adopted in all levels of education and especially in higher education (Kirkpatrick, 2017). EMI is defined as the classroom language used by teachers to teach content subjects in mathematics, economics, and science despite English not being the students and teachers’ first language. Three basic reasons underly the establishment of EMI in higher education. First, it encourages students to acquire a higher level of English proficiency (Dearden, 2018; Doiz & Lasagabaster, 2018; Rose et al., 2019). Second, it prepares students for better future jobs (Galloway et al., 2020; Kirkpatrick, 2017; Spolsky, 2004) and to become international employers (Coleman, 2006; Crystal, 2003; Hu et al., 2014). Third, it accommodates the increased global demand for academic research and teaching materials which is dominantly in English (Liu, 2017; Montgomery, 2015).

Previous studies on EMI in higher education settings have yielded positive findings related to the enactment of EMI recently (Chou, 2018; Lee et al., 2004). Floris (2014) and Simbolon (2018) state that EMI is very important for higher education graduates since it contributes to students’ English language proficiency. This can be regarded as a perceived benefit and benchmark of a ‘successful’ EMI (Dearden, 2018; Rose et al., 2019) since it becomes one of the fundamental criteria to determine the success of a program (Aizawa & Rose, 2019; Macaro et al., 2018). Furthermore, Kim (2014) found that students responded positively to the overall learning atmosphere, learning motivation, and supplementary materials in EMI classes.

Nevertheless, numerous challenges arise when implementing EMI programs at universities around the globe (Macaro et al., 2018) for both students and lecturers (Jiang et al., 2019). Lecturers do not treat themselves as language instructors and are not able to give their students linguistic feedback because of their inadequate English proficiency (Macaro & Akincioglu, 2018). Therefore, students receive less support and instruction from their lecturers (Byun et al., 2011; Wu, 2006). These language-related challenges encounter barriers to the teaching and learning process because of reduced interaction between lecturers and students with limited English proficiency. Floris (2014) and Kim (2012) reported that lecturers had negative responses towards EMI because of the increased workload and the need to work hard to prepare teaching materials in English. In a similar vein, students had difficulties understanding lecturers in English (Evans & Morrison, 2011), and had an increased workload and limited coverage of content when using English (Tatzl, 2011).

Due to the evidence above, it is important to further investigate students' perceptions regarding their awareness and willingness to participate in EMI classes. In addition, there is a need to determine if students’ perceptions of EMI change with more exposure to English instruction since none of the existing research has reported results on that particular topic. No previous studies have investigated if the number of semesters students have studied English and the resultant influence on their perceptions of EMI. This has led to the development of the research questions, which form the basis of this study:

Are there any significant differences in students’ perceptions of EMI, depending on the lengths of English instruction, and how different are the perceptions of students with different amounts of experience studying English?

Methods

Research design

This present study used a mixed-methods approach. This approach was chosen to strengthen each method, give a multi-analysis of issues, and improve the validity (Dörnyei, 2007). A descriptive quantitative method was employed to investigate students’ perceptions of EMI across their years of learning experiences. In addition, a qualitative method was used to confirm their perceptions obtained from the quantitative data.

Participants

The participants were non-English major undergraduate students at a well-known state university in Indonesia. They were from two different Economics and Business classes where full EMI was implemented. There were two groups: Group A consisted of 13 first-year students who had experienced EMI for two semesters; and Group B, with 11 junior students who had received EMI for six semesters. A convenience sample was used since the students were available to participate in the study and support for their participation was given by their lecturer.

The study was approved by the head of the Economics and Business Faculty and the Vice-Rector of Academic Affairs of the university. A written informed consent letter was obtained from all participants who volunteered to take part in the study. The individual questionnaires and interview data were kept confidential, coded, and were only accessible to the research team.

Research instruments

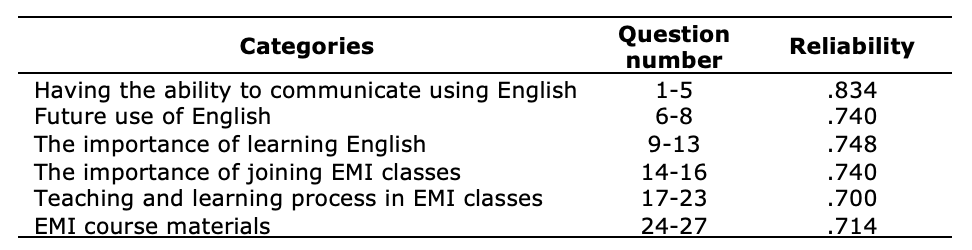

A quantitative guided questionnaire was used to collect data on students’ perceptions of EMI which was adapted and modified from Subekti (2018) in terms of the total number of the items and the categories. There were 27 items, grouped into six specific categories: having the ability to communicate using English (5 items), future use of English (3 items), the importance of learning English (5 items), the importance of joining EMI classes (3 items), teaching and learning process in EMI classes (7 items), and EMI course materials (4 items). Subekti’s items had been grouped into three categories. A five-point, Likert scale consisting of Strongly Agree, coded as 5, Agree (4), Neutral (3), Disagree (2), and Strongly Disagree (1) was used.

The students’ interview guide was used to get more in-depth information about students’ experiences in EMI classes. Six interview questions, derived from the questionnaire, were constructed to confirm the questionnaire’s results. The six questions dealt with (1) the importance of English and learning English, (2) the future use of English, (3) the necessity of having the ability to speak English, (4) the possibility of joining EMI classes, (5) teaching and learning processes in EMI classes, and (6) the EMI materials.

Data collection

Data collection was carried out in January 2020, two months before the beginning of the Covid 19 pandemic in Indonesia at a time when face-to-face classes were still being used. The first step was getting a statement of the students’ willingness to take part in the research. Then, the questionnaire was distributed to the students. Before the distribution, the students were told how to complete the questionnaire. They had no time limit to complete it and if necessary, had the opportunity to ask questions concerning it. The questionnaire was written in English and given to both groups at different times without distracting their classes.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted after the participants had completed the questionnaire. Four students were recruited at random for an interview with the researchers. Before accepting to be interviewed, the participants were given information about the project, the interview guide, and the issues concerning a wide range of questions about their work as EMI students. It was emphasized that their participation was voluntary and that the data obtained would be used for scientific purposes only. It was also explained that the participants would be anonymous so that no individual student could be identified in articles or other texts. The interviews were conducted for about 15 minutes in Indonesian, the language that the participants felt most comfortable using.

Data analysis

To compare and find out the differences in students’ perceptions of EMI of Group A and Group B, the quantitative data were tabulated using a Microsoft Excel (version 365) and analyzed using SPSS 21.0 for Windows. Since the number of items for each subscale was different, the mean score of each category was standardized by dividing the number of questions. To determine whether the mean scores had a significant difference, an independent sample t-test was employed with the alpha level set at .05.

The interview data were recorded and lasted about 15 minutes for each participant. The recordings were transcribed, and then the results of the transcriptions were delivered to the participants to confirm that no points were considered confusing. The excerpts were then translated into English. To maintain anonymity, detailed information which could reveal the participants’ identities was deleted or changed, and the participants were named as S1A (Student 1 of Group A), S2A (Student 2 of Group A), S1B (Student 1 of Group B), and S2B (Student 2 of Group B). Interpretive qualitative analysis was directed at reading the interview transcripts repeatedly to understand the contents of the interviews.

Results

Descriptive statistics and an independent-sample t-test were conducted to examine whether the EMI perceptions of students with different timespans of exposure to English instruction show significant differences. As determined by Cronbach’s alpha, a test of internal consistency, the questionnaire was considered reliable as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Questionnaire instrument

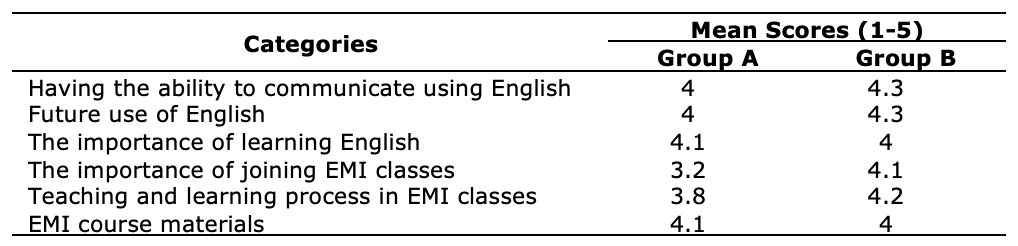

The questionnaire consisted of 27 items, classified into six categories. The statistical results of the questionnaire were shown in the mean scores of all categories for Group A and Group B. The overall results are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Students’ perceptions of each category of Group A and Group B

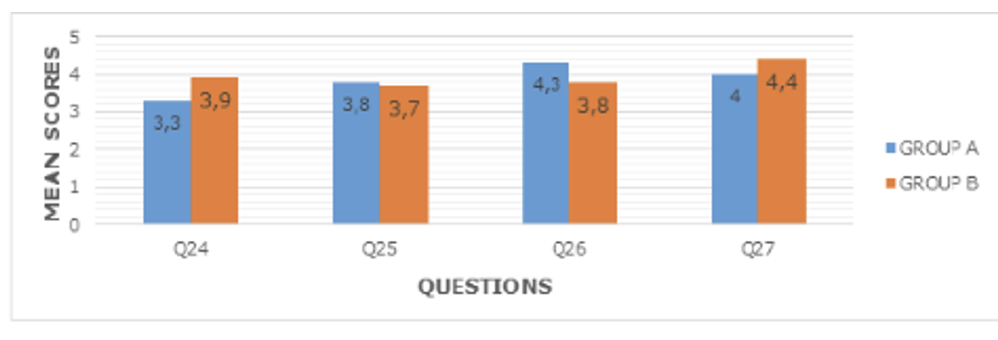

Figure 1 provides visual results of students’ perceptions in each category.

Figure 1: Students’ perceptions of EMI between Group A and Group B

The overall data in Figure 1 show that the mean scores of students’ perceptions between Group A and Group B vary. In Group A (the Group with less exposure to English instruction), the categories EMI course materials and the importance of learning English have the highest mean (4.1) while the category the importance of joining EMI classes has the lowest mean (3.2). In Group B (the group with greater exposure to English instruction), the categories having the ability to speak English and future use of English have the highest mean (4.3). The lowest mean score was the category of the importance of learning English and EMI course materials (4.0). From the results, it can be said that each Group had different high means and low means in different categories. The overall mean scores in the categories of both groups were above 3.0 which means that the students’ perception tends to be positive relating to the scale code of the questionnaire. The results for each category are outlined in the following sections.

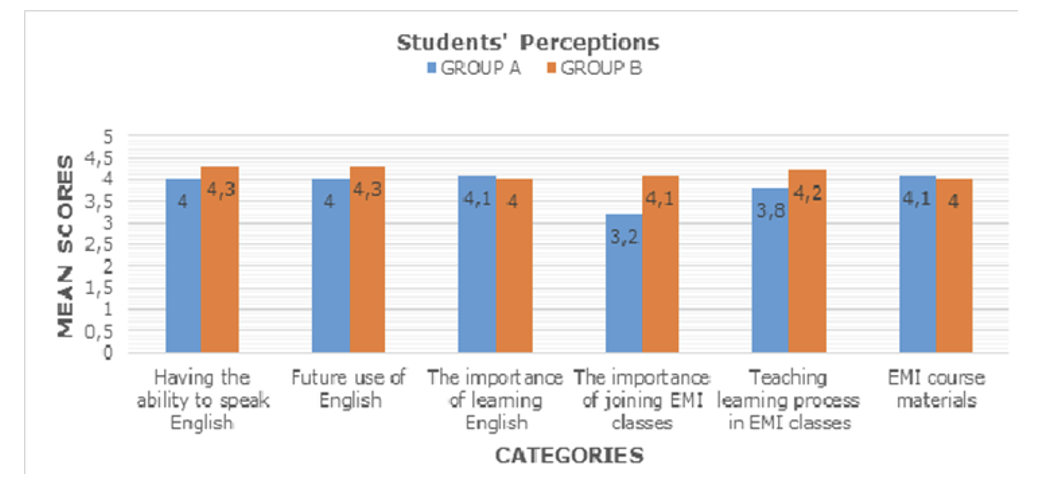

Having the ability to speak in English

Five items, I.1 to I.5 (See Appendix) were used to gather data on students’ perceptions. See Figure 2 for each of the mean scores for Group A and Group B.

Figure 2: Students’ perceptions of each question for Group A and Group B

Figure 2 shows that the mean scores of the perceptions for Group A are lower than for Group B. It is interesting that I.4 of both groups, I can imagine myself speaking English with international friends or colleagues has the highest mean of all. In the same way, I.5, I can imagine myself speaking English as if I were a native speaker of English, both Groups have the lowest mean of all. Overall, both groups tend to agree on the importance of having the ability to communicate in English.

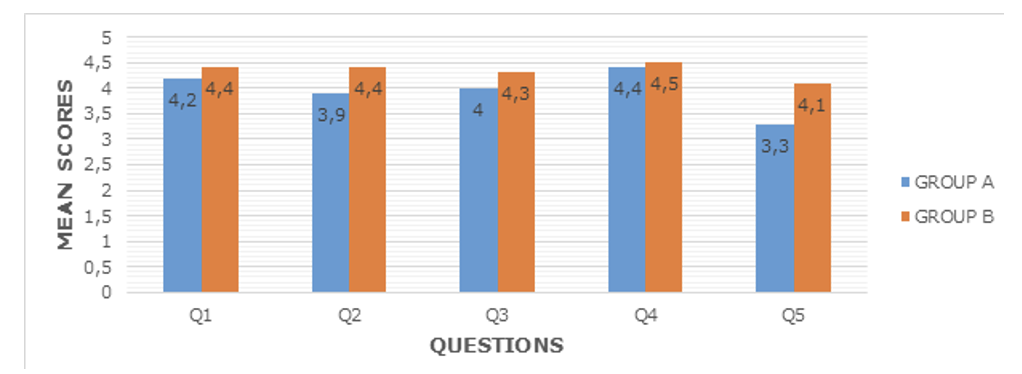

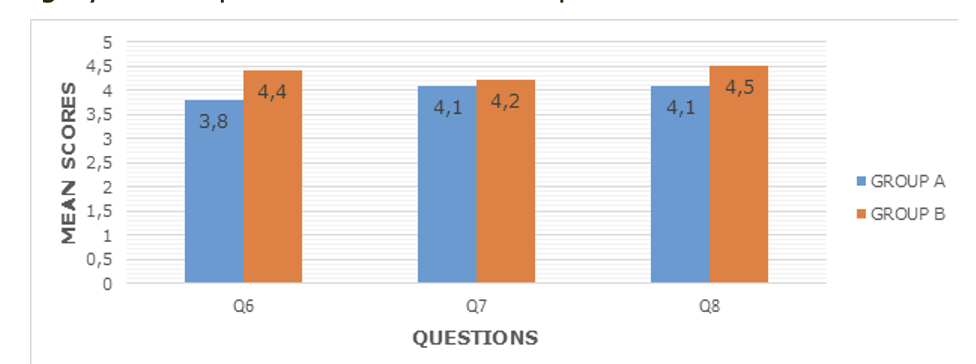

Future use of English

Three items I.6 to I.8 were used to gather data for this category. Figure 3 shows that all the means of the items in the category of Group A are lower than Group B.

Figure 3: Students’ perceptions of each question for Group A and Group B

It is interesting to find that I.8, I can imagine myself studying in a university where all my courses are taught in English,had the highest score in both groups. However, they have different items with the lowest mean. Group A’s lowest mean was I.6, whenever I think of my future career, I imagine myself using English. while group B’s lowest mean was I.7, the things I want to do in the future require me to use English.

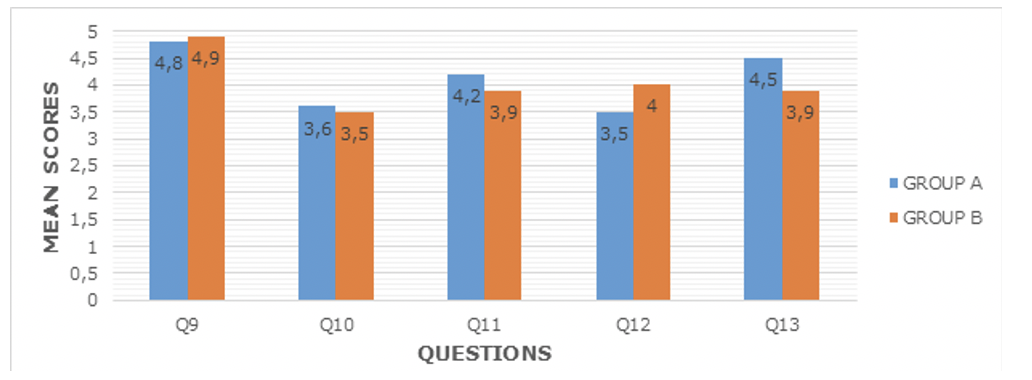

The importance of learning English

Five items, I.9 to I.13, were used to measure perceptions on the importance of learning English.

Figure 4: Students’ perceptions of each question for Group A and Group B

Figure 4 indicates that I.9, I study English because I think it is important, had the highest score in both Groups. However, the lowest score was different in both Groups. In Group A, I.12, I will have a positive impact on my life if I learn English had the lowest score (3.5). In Group B, I.10, I agree that learning English is necessary because people around me expect me to do so, had the lowest score (3.5).

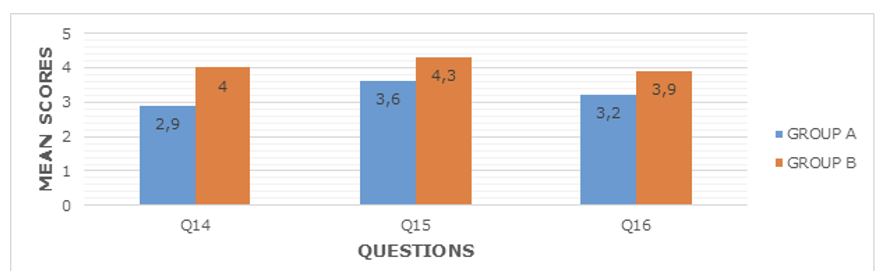

The importance of joining EMI classes

Two items, I.14 to I.16 were used to gather data for this category.

Figure 5: Students’ perceptions of each question for Group A and Group B

Figure 5 shows that Group A had a lower mean than Group B for each item in the category and I.15, joining EMI classes is important to me to be an educated person had the highest mean in both Groups. I.14, joining EMI classes is important to me to gain acknowledgment of my teachers and peers had the lowest mean.

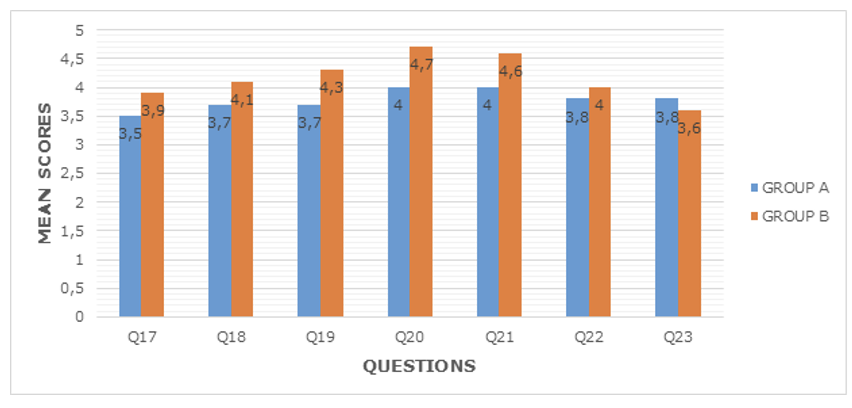

Teaching and learning process in EMI classes

Seven items, I.17. to I.23 were used to measure perceptions of the category.

Figure 6: Students’ perceptions of each question for Group A and Group B

Figure 6 indicates that almost all means for Group A are lower than for Group B. I.20, I find learning English very interesting, had the highest mean of all items, followed by I.21, I really enjoy learning English. In addition, the item’s lowest mean of each group was different. The lowest mean for Group A was I.19, I like the atmosphere in my EMI classes (3.7), while for Group B it was I.23, I like my English teacher because of his/her fun English class (3.6).

EMI course materials

Four items, I.24 to I.27 were used to collect data for the category.

Figure 7. Students’ perceptions of each item in the category for Group A and Group B

It is the only item that Group A has a higher mean than Group B. It is interesting to find that both Groups have the lowest means in I.25, the level of difficulty of English materials helps me improve my English.

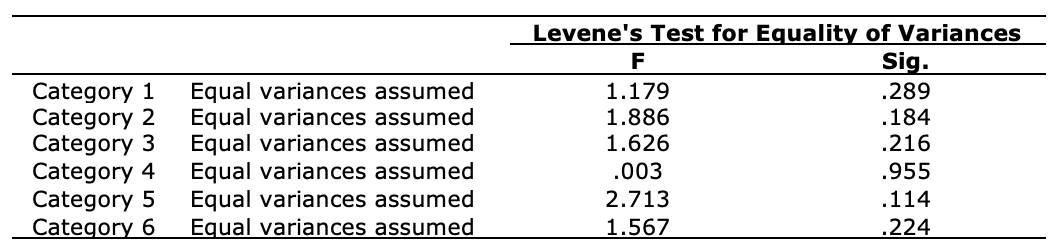

Based on the descriptive statistical analysis, it was revealed that Group A and Group B have different perceptions. To find out whether the mean scores between Group A and Group B have significant differences or not, an independent samples t-test was calculated. To test the homogeneity of the students, as one of the required assumptions in the independence samples t-test, the Levene test was employed. The result of the Levene test is presented in Table 3.

Table 3: The result of the Levene test

Table 3 shows that the significant values for all categories are more than .05, meaning that the variance of the two groups in each category is equal. Then, an independent samples t-test was run to compare the mean scores of students’ EMI perceptions between Group A and Group B. The result of the analysis is shown in Table 4.

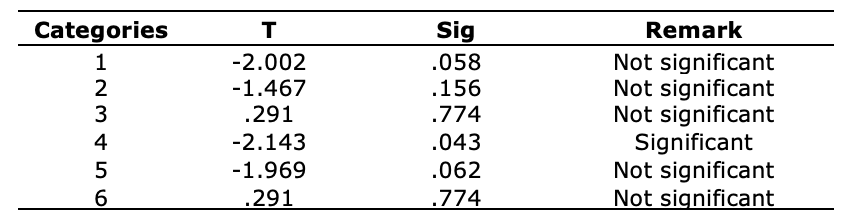

Table 4: The result of independent samples t-test

In general, the results of the analysis in Table 4 showed that the mean scores of five out of six categories; categories 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 were higher than .05 as the significance level. It revealed that there was no significant difference in the perception of EMI between Group A and Group B in those categories although both Groups had had English instruction in EMI classrooms for different lengths of time. On the other hand, the mean score of category 4 was less than .05 as the significance level, meaning that there was a significant difference in the perceptions of EMI. Therefore, to find out the comparison of the mean score for all categories, Table 5 shows the result of independent samples t-test between Group A and Group B.

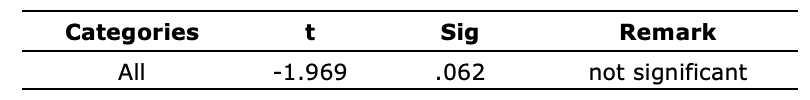

Table 5: Independent Sample t-test for all categories in Group A and Group B

The result showed that the significance value for all categories in Group A and Group B was higher than .05. It revealed that there was no significant difference between the perceptions of Group A and B on EMI regardless of their different lengths of time of getting English instruction in EMI classrooms.

Similar results of students' perceptions on EMI were obtained from interviews with two students from Group A and two students from Group B. All the participants agreed that English was very important for them since it was considered an international language and a means to build communication among people around the world. S1A, for example, emphasized the importance of English, not only for communication but for someone’s future career as well,

I can say for sure that English is very crucial nowadays for globalization and internationalization. Everybody around the world shares information each other and communicates using English since it is considered as an international language. I also found that almost all job required their workers/employees to speak English well since it is urgently needed for companies to compete with others internationally. (S1A)

S2A added that the ability to speak English was very necessary when abroad.

The ability to speak in English becomes an absolute need when living abroad since it is used globally by people. We could survive living in other country if we understood what to say and how to respond to others. (S2A)

Another participant, S1B highlighted the urgency of learning English. She believed that learning English and joining EMI classes gave her greater opportunities to practice English.

Joining EMI classes offered me greater opportunities to learn English and to get maximum English exposure. I could read the course materials in English, listen to the lecturer’s explanation in English, and practice English all the time and even give a class presentation. Furthermore, in the future, I say confidently that having good English will be widely required for applicants to apply for jobs. (S1B)

S2B said firmly that EMI classes helped him to acquire English more easily than not joining EMI classes.

By joining EMI classes I could increase my knowledge in English. I think people around me consider me as an educated person when I can show my ability in English. I could not imagine myself if I didn’t take EMI program. My English would be worse. (S2B)

S1A and S2B further said their enjoyment while working in EMI classes.

So far, I feel comfortable studying in EMI classes because the EMI teachers were very helpful if I had problems understanding the course materials (S1A). Friends of mine also invited me to have discussions with them to find solutions for difficult materials. Such a good learning environment motivated me to learn more in EMI classes. (S2B)

Discussion

Based on the overall results, it can be drawn as a general conclusion that students’ responses to English as a language of instruction in the classroom tended to fall to either "Strongly Agree" or "Agree" among the students of Group A and Group B despite having different lengths of experiences in learning English. The results indicated that both Groups had positive perceptions towards the implementation of EMI; no significant differences in their perceptions were found. Students’ opinions in the interview results of both groups were also positive, showing their agreement about the EMI program.

The categories having the ability to communicate using English and future use of English had the highest mean (4.3). Based on the interview results, the participants considered the importance of English in the globalized era. They felt that acquiring English enabled them to communicate with others visiting from foreign countries and if they were to live abroad. They were also aware of the necessity of English for their future careers. These results are consistent with the ideas of Floris (2014), Kirkpatrick (2017), and Simbolon (2018) that students realize the importance of English for their future life.

Concerning the category of the importance of learning English, the mean scores of both groups were 4 and 4.3. They agreed that it was important to learn English. The interview results showed that all the participants indicated the importance to learn English since it has become the main requirement to apply for a job. Furthermore, one of the participants stated that he would get a good job easily if he were good at English.. The high employability as the result of learning English supports the previous studies conducted by Coleman (2006), Crystal (2004), Floris (2014), Hu et al. (2014), and Simbolon (2018), reporting that learning English is urgently needed for students’ future in the workplace.

An interesting finding related to Category 4, the importance of joining EMI classes, shows significant perceptions held by the students. They thought that one reason for joining EMI classes was to get teachers’ and peers’ acknowledgment since they believed that joining EMI classes could equip them with a good English proficiency to prepare them to get better work opportunities in the future. In the interview results, it was revealed that the students felt they were able to use English fully in EMI classes helping them acquire more. The results have confirmed the findings of Kirkpatrick (2017) and Galloway et al. (2020) that students are aware of the importance of joining EMI classes to improve their English proficiency to increase their general education.

The general results of students’ perception in the category the teaching and learning process in EMI classes showed that the students of both Groups tended to give positive responses. The students agreed in the questionnaire and interview that their EMI teachers were good and their classmates were very helpful. Their assistance motivated them to study in their EMI classes. This is in line with Kim (2014) who stated that a positive learning atmosphere and learning motivation were found in EMI classes. These positive and motivating factors lead to the improvement of students’ English proficiency (Galloway et al., 2020) .

The final category is EMI course materials. Based on the general result of the category, the students of both Groups tended to give positive responses to EMI materials. The students felt that the EMI materials suited their needs and improved their English and academic achievement. The findings seemingly contradict with the results of the studies done by Evans and Morrison (2011) and (Tatzl,2011) who reported that students felt burdened and found it difficult to understand the material in English since they had limited English proficiency.

Limitations of the study

The present study is limited in the number of participants since the EMI classes in this research setting are generally small. The data obtained would be more in-depth if the questionnaire was carried out in a larger number of students.

Implications and recommendations

Future researchers are recommended to conduct a similar study with larger samples of participants or develop more categories in the questionnaire to examine the teachers’ points of view, related to the challenges and strategies in the EMI classroom. Also conducting a study on the effectiveness of the EMI program for students’ academic achievement and language performance could also be an alternative.

Conclusion

The present study was examined the students’ perceptions on EMI based on the different lengths of time they had had English instruction. The results showed that students in Group A and Group B who had studied for different lengths of time in EMI classes tended to give positive responses to EMI, but there were no significant differences between the two groups' perceptions. All students agreed that having English instruction in EMI classes was important for their future. The positive results of students’ perception in this study can be considered when defending EMI implementation in higher education. The results suggest that EMI in higher education must be continued since it apparently equips students with an ability to communicate in English.

References

Aizawa, I., & Rose, H. (2020). High school to university transitional challenges in English medium instruction in Japan. System, 95, 102390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102390

Byun, K., Chu, H., Kim, M., Park, I., Kim, S., & Jung, J. (2011). English-medium-teaching in Korean higher educations: Policy debates and reality. Higher Education, 62(1), 431-449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9397-4

Chou, M.-H. (2018). Speaking anxiety and strategy use for learning English as a Foreign Language in full and partial English-medium instruction contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 52(3), 611-633. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.455

Coleman, J. A. (2006). English-medium teaching in European higher education. Language Teaching, 39(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480600320X

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Dearden, J. (2018). The changing roles of EMI academics and English language specialists. In Y. Kırkgöz & K. Dikilitaş (Eds.), Key issues in English for specific purposes in higher education (pp. 323-338). Springer.

Doiz, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2018). Teachers’ and students’ second language motivational self-system in English-medium instruction: A qualitative approach. TESOL Quarterly, 52(3), 657-679. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.452

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in Applied Linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press. https://thuvienso.hoasen.edu.vn/handle/123456789/14893

Evans, S., & Morrison, B. (2011). Meeting the challenges of English-medium higher education: The first-year experience in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes, 30(3), 198-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.01.001

Floris, F. D. (2014). Learning subject matter through English as the medium of instruction: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Asian Englishes, 16(1), 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2014.884879

Galloway, N., Numajiri, T., & Rees, N. (2020). The ‘internationalisation’, or ‘Englishisation’, of higher education in East Asia. Higher Education, 80, 395-414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00486-1

Hu, G., Li, L., & Lei, J. (2014). English-medium instruction at a Chinese University: Rhetoric and reality. Language Policy, 13(1), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-013-9298-3

Jiang, L., Zhang, L. J., & May, S. (2019). Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: Teachers’ practices and perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(2), 107-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231166

Kim, E. G. (2014). Korean engineering professors' views on English language education in relation to English-medium instruction. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 11(2), 1-33.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2017). English medium instruction in higher education in Asia-Pacific: From policy to pedagogy. In B. Fenton-Smith, P. Humphreys, & I. Walkinshaw. (Eds.). English Medium Instruction in Higher Education in Asia-Pacific: From Policy to Pedagogy. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51976-0

Lee, E., Kim, K., & Jung, Y. (2004). Major courses taught in English: a survey for effective EMI. Technical Report 04-1. Postech Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning.

Liu, W. (2017). The changing role of non-English papers in scholarly communication: Evidence from Web of Science's three journal citation indexes. Learned Publishing, 302), 115-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1089

Montgomery, S. L. (2015). Does science need a global language? English and the future of research. Technology and Culture, 56(1), 261-263. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2015.0013

Macaro, E., & Akincioglu, M. (2018). Turkish university students’ perceptions about English medium instruction: Exploring year group, gender and university type as variables. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(3), 256-270.https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1367398

Macaro, E., Curle, S., Pun, J., Jiangshan, A., & Dearden, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36-76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000350

Mukminatien, N. (2012). Accommodating world Englishes in developing EFL learners’ oral communication. TEFLIN Journal, 23(2), 222-232. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v23i2/222-232

Rose, H., Curle, S., Aizawa, I., & Thompson, G. (2019). What drives success in English medium taught courses? The interplay between language proficiency, academic skills, and motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 2149-2161. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1590690

Simbolon, N. (2018). EMI in Indonesian higher education stakeholders’ perspective. TEFLIN Journal, 29(1), 108-128. https://doi.org/10.15639/teflinjournal.v29i1/108-128

Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Subekti, A.S. (2018). L2 motivational self-system and L2 achievement: A study of Indonesian EAP learners. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 57-67. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v8i1.11465

Tatzl, D. (2011). English-medium masters’ programmes at an Austrian university of applied sciences: Attitudes, experiences and challenges. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(4). 252-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.08.003

Wu, W.S. (2006). Students' attitude toward EMI: using Chung Hua university as an example. Journal of English and Foreign Language and Literature, 4(1), 67-84. https://doi.org/10.6372/JEFLL.200612.0067